Current legal systems for governing data are under stress which is not surprising given the speed of technological changes underway. While there is no immediate failure of the law the present legal regime is not capable of meeting the future challanges of data governance and requires to be reformed.

Data production and dissemination takes place in a globalised, interlinked, and distributed network. A dataset yields knowledge to the extent it can be linked to another dataset, which then can be linked to another dataset, and so on. A key challenge for data governance is to find mechanisms for allocating responsibilities across this complex network of data pollination. At the same time, large multinational organizations are leading the development and uptake of technology, leaving the rest of society at the receiving end of innovation.

In this climate of uncertainty and tensions getting the balance right is of utmost importance.

In Europe, multiple agile legal initiatives for establishing and implementing a comprehensive strategy for data have been penned out acknowledging that the availability of more and better data can simultaneously accelerate private initiatives and create benefits for the public. The goal is an overarching management framework for economic activities with and around data based on Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable principles.

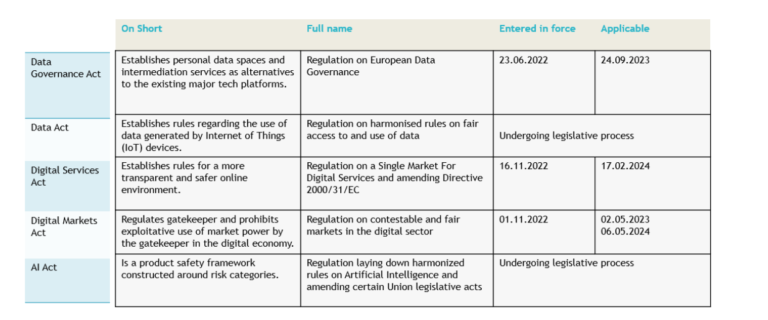

This is to be achieved in practice by a set of interdependent legal instruments, most notably:

- The Data Governance Act, creating processes and structures to facilitate voluntary data sharing by companies, individuals, and the public sector.

- The Data Act, establishing rules and conditions for a fairer access to and reuse of data from industry, including Internet of Things (IoT).

- The Digital Services Act, creating rules to prevent illegal content and increased traceability and accountability of traders on online marketplaces.

- The Digital Markets Act, setting up rules for digital gatekeepers to ensure open markets; and

- The AI Act cautioning a risk-based approach to for providers, users, importers, and distributors of AI systems.

The Data Governance Act regulates the safe reuse of public data, typically, subject to the rights of others. This includes, protected data such as, trade secrets, personal data, and intellectual property rights. Entered in force on 23 June 2022 it will be applicable across members states starting with 24 September 2023.

The legislator focuses its attention on incentivizing the use of data rather than preventing its misuse, by addressing the following strategic points:

- Making public sector data re-usable when such data is subject to third-party rights.

- Data sharing among businesses in exchange for remuneration in any form.

- Allowing personal data to be used with the assistance of intermediaries, intended to support individuals in exercising their rights under the General Data Protection Regulation

- Allowing for the creation of personal data spaces and the use of data based on altruism.

Each time data is shared, accessed, or used, several stewardship activities take place, such as, finding data that is fit-for-purpose, managing transfers and usage rights, and ensuring that data protections are in place. Intermediaries provide technical infrastructure and expertise to support interoperability between datasets, or act as a mediator in negotiating arrangements between parties interested in sharing, accessing, or pooling data.

Intermediaries facilitate user control over data. Users are provided with the ability to download data from a platform and provide access to the data to another platform. Users decide what data sharing is beneficial to them, and under which terms. Users are accumulating data in private vaults, data spaces or data wallets based on the data holder’s consent or authorization. Users allow third parties to access data only when it is associated with sufficient benefits to users.

Users, and not initial data collectors or other companies, determine who gets access to the data.

This is an important changing of the structure of data flows.

The legislator facilitates voluntarily sharing of data for common good, such as for medical research projects, enriching education, reduced inequalities, etc. Entities seeking to collect data for objectives of general interest may request to be listed in a national register of recognised data altruism organisations.

The Data Act currently pending legislative process aims at establishing rules for the use of data generated by the Internet of Things (IoT) devices. Adoption of the Data Act is anticipated by mid-2023, and the current proposal provides only a 12-month implementation period.

Through the powerful engagement of this legal instrument the legislator creates the premises to provide consumers of smart devices with access to data generated by their own use of such devices. Users can order a manufacturer to share their data in real-time with third parties whose non-competing services users wish to consume. Users seem to be very free in terms of how they use the data they get access to. There is only one limit: data cannot be used to develop products that compete with the products from which the data originated.

Regarding the sharing of data with third parties, users are not allowed to share data with businesses designated as gatekeepers under the Digital Markets Act to avoid increasing their economic power through more data. The law is intended to avoid SMEs being able to use access to data to reverse engine a rival’s product to launch a direct clone.

Furthermore, the law aims at protecting SMEs against unfair contractual terms being imposed on them by more powerful platforms and market players to extract most valuable data. For that matter, the law stipulates a list of unilaterally imposed contractual clauses that are deemed to be unfair, such as a clause providing that a contractual party can unilaterally interpret the terms of the contract. Under the law non-binding model contractual clauses will be developed and recommended to help SMEs negotiate fairer and balanced data sharing contracts with companies enjoying a significantly stronger bargaining position.

On top of that, the law empowers users to effectively switch between different cloud data-processing services providers by advancing new contractual obligations for cloud providers, and a new standardisation framework for data and cloud interoperability. The main objective here is to make it easier for users to move their data and applications from one cloud provider to another without incurring any costs.

Last, the law sets clear rules for scenarios when governments and public sector organizations can access IoT data such as in public emergencies cases.

The Digital Services Act has been appreciated by professionals as being an asymmetric by design risk-based regulation of online platforms relying on the principle that larger platforms, specifically very large online platforms (or VLOPs), must comply with more stringent due diligence, transparency and reporting obligations compared to smaller platforms. It builds on the e-Commerce Directive to ensure that what is illegal offline is equally illegal online. It entered into force on 16 November 2022 and will become applicable starting with 17 February 2024.

In the past years, Member States have increasingly introduced legislation on digital services and online platforms to supervise them and reduce the harms associated with the spread of illegal content. Therefore, one of the main drivers of this law is to limit the normative fragmentation resulting from the initiatives undertaken at the national level. For instance, national laws such as the German Network Enforcement Act, the French Online Hate Speech Law and the Austrian Anti-Hate Speech Law have imposed more stringent obligations on the platforms, requiring them, under the warning of high fines, to ramp up their efforts in limiting the spread of certain types of illegal content, including illegal hate-speech. All these national level initiatives have caused fragmentation and legal uncertainty on the liability regime applicable to providers, affecting smaller service providers and hindering their capability to compete effectively on the market.

New compliance obligations include mandatory notice-and-action requirements, own-initiative investigations, assessments of systemic risks, mandatory redress for content removal decisions, trusted flaggers, user complaints and account suspension and a comprehensive risk management and audit framework.

The Digital Markets Act entered into force on 1 November 2022 and will become applicable, for the most part, on 2 May 2023. It aims at ensuring that markets remain open to new entrants, despite the presence of platforms with gatekeeper power, and fair by prohibiting exploitative use of market power by gatekeepers.

In the current context, the rise of powerful gatekeepers controlling the main online platforms had led to sub-optimal levels of innovation. Essentially, the innovation incentives of the gatekeepers and the users become misaligned, and the gatekeepers start to divert some of their efforts towards preventing or appropriating innovations brought about by others. The main concern is that the platform gatekeepers would go out of their way to control the flow of innovation around their platforms. While blocking inventive offerings by users is certainly possible a more likely course of conduct is that the gatekeepers would use bundling or self-preferencing to exclude the inventive user and appropriate the profits from the innovation via a competing offering of their own.

Therefore, the law will subject gatekeepers to obligations and prohibitions drawn from a list of dos and don’ts. Specifically, gatekeepers will be obliged to refrain from a series of conducts, such as: combining the personal data from their core services with the personal data sourced from other services offered by them or by third parties; requiring the business users to use identification services of the gatekeeper for services they offer through the gatekeeper’s core platform services; making the use of a core platform service by business users and end users conditional upon the subscription to another core platform services; using data generated on the platform by business users in competition with the latter and discriminating in rankings products and services offered by third parties.

The AI Act is a product safety framework constructed around risk categories. The law is currently pending legislative process and is scheduled to be voted by end of March 2023.

The compliance regime relies on dedicated actors, as well as on specific requirements and control modalities. The high-risk AI systems provider is the principal responsible party defined as a natural or legal person, public authority, agency, or other body that develops an AI system or that has an AI system developed with a view to placing it on the market or putting it into service under its own name or trademark, whether for payment or free of charge. The manufacturer of the product can also be made responsible when an AI system is linked to safety products and placed on the market under the name of the manufacturer. In this case, the manufacturer is responsible for the conformity of the AI system and has the same obligations as the provider.

Finally, importers and distributors are obliged to verify that the provider has complied with its obligations, while users have rights but also assume some obligations. The national inspection authorities are the notifying authorities that designate and notify the assessment bodies whose task is essentially to carry out an external conformity assessment. More broadly, the national competent authorities will have to ensure the application and implementation of the law. The European Artificial Intelligence Board will be a cooperation and coordination body and will provide help and assistance to the E.U. Commission which will be chairing it. It will be composed of the European Data Protection Supervisor and the competent national authorities.

The law creates new conformity obligations, largely based on the technicality of high-risk AI systems themselves, but also on the technicality of certification and standardization mechanisms.

The legislator provides that high-risk AI systems must as a minima follow conformity assessment procedures before they can be placed on the Union’s market in order to minimize the following risks: confidentiality and data analysis, precision, robustness, resilience, explicability, non-discrimination.

Manufacturers of an AI systems will have to manage large amounts of data, including personal data for which they must guarantee their integrity and confidentiality. From a technical point of view, confidentiality can be achieved either by pseudonymization or by anonymization, in conformity with the GDPR provisions.

Data governance obligations are part of the law if high-risk AI systems use techniques involving learning models with data based on training, validation, and test datasets. Datasets must be reliable, which is why the law imposes that training, validation and testing data sets to be subjected to appropriate data governance and management practices, such as the relevant design choices, annotation, labelling, cleaning, enrichment and aggregation, a prior assessment of the availability, quantity and suitability of the data sets that are needed, examination in view of possible biases, the identification of any possible data gaps or shortcomings, and how those gaps and shortcomings can be addressed, transparency on the source of the datasets, their reach and key characteristics, how the data were obtained and selected, etc.

Furthermore, the legislator establishes rules for a graduated risk management to help technical operators meet their obligations. A risk management system consisting of an iterative, continuous process conducted throughout the life cycle of a high-risk AI system must be established, implemented, documented, and maintained. The management system consists mainly of obligations to identify and minimize foreseeable risks, to manage residual risks and tests. Risk minimization is based on the adoption of suitable measures as reflected notably in relevant harmonised standards or common specifications. Residual risks are considered acceptable, provided that the high-risk AI system is used for its intended purpose or under conditions of reasonably foreseeable misuse. The user must be informed of these residual risks, while risk minimization or mitigation measures must be taken. High-risk AI systems must be tested, to determine the most appropriate risk management measures at any time during the development process and, in any case, before being placed on the market or put into service, based on previously defined metrics and probabilistic thresholds adapted to the purpose of the high-risk AI systems.

Conclusion

Economies stand to benefit greatly from the opportunities afforded by data integration, but also suffer from the challenges associated with the fast-paced evolution of knowledge that the technological developments have recently injected into the field. The evergreen technological context is prone to create important tensions regarding the way data is managed and used. The significance of these tensions is growing, and potential implications are accumulating.

This means that in policy, law, and public discourse notions such as accountability, agency, consent, privacy, and ownership will continue to change. In some areas society cannot yet frame meaningful questions around these issues, but actions are being taken now that will have long-term and cumulative effects, providing for a level playing field for all stakeholders. At this moment, as Europe takes the initiative, we can only guess at the effects of a FAIR data economy while taking the leap forward and embarking on new initiatives. Alongside the powerful, effective, and deeply moral approach to regulating the data economy, it is time to build on early success of the GDPR and create a European data economy that is both FAIR and effective.

Resources:

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A European strategy for data https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0066

- A European Approach to the Establishment of Data Spaces https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC130390

- Personal Data Spaces: An Intervention in Surveillance Capitalism? https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326616606_Personal_Data_Spaces_An_Intervention_in_Surveillance_Capitalism

- KU Leuven White Paper on the Data Governance Act https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352690055_White_Paper_on_the_Data_Governance_Act

- Data management and use: Governance in the 21st century A joint report by the British Academy and the Royal Society https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/documents/105/Data_management_and_use_-_Governance_in_the_21st_century.pdf

- Stanford Law School, EU Artificial Intelligence Act: The European Approach to AI https://law.stanford.edu/publications/eu-artificial-intelligence-act-the-european-approach-to-ai/

Author Petruta Pirvan, Founder and Legal Counsel Data Privacy and Digital Law @EU Digital Partners